Dr. Clay Robinson was a professor of soil and crop sciences at West Texas A&M for 17 years. While at WTAMU, one of his main interests was the influence of climatic conditions on farming, particularly dry land and crop-fallow systems. After leaving the University, he spent a couple years working in the private sector. Currently, he is the Agronomy and Soil Science Education Manager for the American Society of Agronomy.

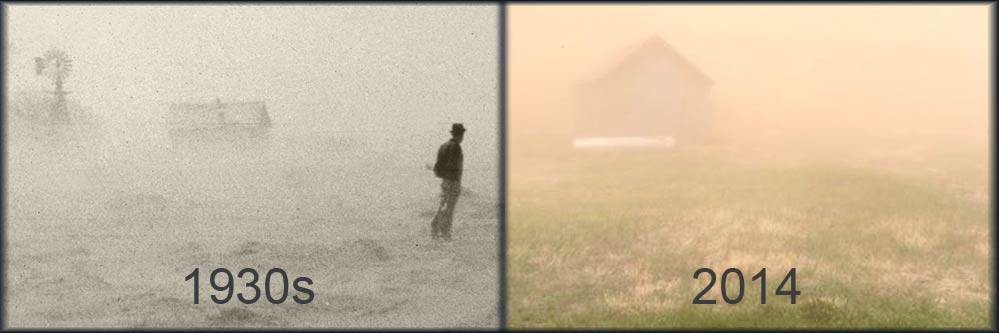

The continuing drought has everyone’s attention, especially with the recent dust storms in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles, southwestern Kansas, eastern New Mexico and southeastern Colorado. Warmer temperatures, higher evaporation rates, and less precipitation have stacked up to create a harsher drought than those of the 1930s and 1950s.

The drought of the Dirty ‘30s lasted seven years. Dust storms were so intense due to the practice of inversion tillage, better known as the overuse of the moldboard and one-way disc plows. These implements left no residue on the surface, so wind easily picked up the dry, loose dirt. Farmers would fallow half their ground every year leaving it bare. Due to little rain, soil erosion, and lack of nutrients, planted crops did not survive, leaving even more bare ground to blow.

It is important to keep in mind that in the midst of those seven years of drought, some years received near-normal amounts of rain. One year of change does not necessarily mean a cycle has ended.

The five year drought from the ‘50s was more intense than that of the ’30s, but the wind erosion and dust storms were not as severe. There are several reasons for this:

- Irrigation was becoming more commonplace.

- There was less land in production due to land being abandoned during the Dirty Thirties.

- A 3-year rotation of wheat, sorghum and fallow was becoming more common. This left only a third of the land in fallow per year.

- Tillage practices changed – utilizing undercutting implements, such as sweeps, which tilled 3-4 inches deep, and left more residue on the surface.

Today, there is even less land in production than in the ‘50s. Some land abandoned by homesteaders is now owned by the government and is part of the National Grasslands. Some land was put into the Soil Bank (a program similar to CRP) in the late 50s and early 60s, while other land was put into CRP. Plus, overall production is higher which produces more residue. Less land is in fallow because of multi-year rotations and tillage practices that conserve more water in the non-crop season. Irrigation is much more common than it was in the ‘30s or ‘50s. Modern tillage systems and no-till farming practices leave even more residue on the surface.

These factors contribute to limiting the severity of another 1930s style Dust Bowl. Unfortunately, simply because dust storms are not as severe does not mean the drought is less intense. In fact, four years into the current drought the trend continues to get hotter and drier. In the ‘50s, precipitation was 52% of normal; but, this drought is only averaging 44% of normal rainfall. The last truly wet year in Amarillo, Texas for example, was in 1961, registering 30 inches of rainfall, with one other year topping 25 inches. Amarillo experienced its driest year ever recorded in 2011.

The soil is air-dry to at least 2-3 feet on fields that have been tilled. One foot of air-dry soil takes 3-4 inches of rain to get back to flush. Under current conditions, it’s likely to take 16-30 inches of rain to replenish the profile, depending upon the soil type.

Below normal rainfall is predicted for most of the summer and fall over this area of the country, with a possible break in August looking a bit more optimistic. After that, it’s anyone’s guess what the weather will bring. Over the past 80 years, the temperature has gotten steadily warmer, rising almost two degrees in that span. There is also a generally decreasing trend in normal precipitation over the past century. At the same time, lake evaporation in the High Plains has increased about 15 inches in the last 60 years, increasing the amount of water required to produce a bushel of grain.

The current four-year drought is proving to be harsher and more intense than droughts of the past. Although trends do not look positive, when looking back at the droughts of the past, we can be confident there will be an end to this cycle and rain will eventually return. Following the droughts of the ’30s and the ’50s, there were periods of significantly above-normal precipitation. The question is, when will we see enough sustained precipitation over time to replenish the parched areas across the High Plains?

Featured Images by: 1930s – NRCSDC01008, U.S. Department of Agiculture, flickr.com; 2014 – Shannon Evans, Crop Quest